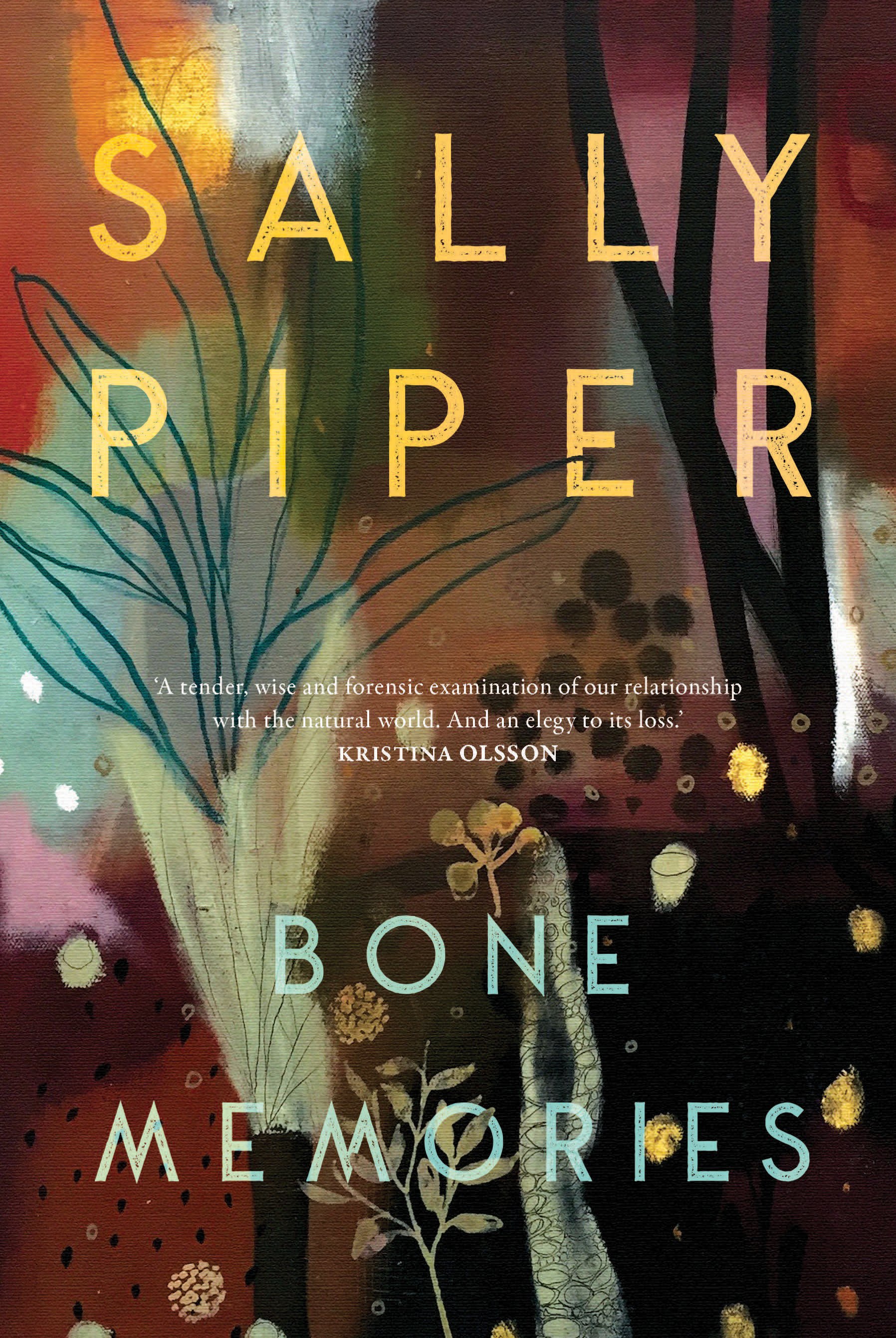

Bone Memories: a family living between stories

by Sally Piper

“…we are between stories…we have forgotten the old way to live but have not yet learnt the new.”

I once read of a Jain nun who swept the path before her with a peacock feather in order to gently clear any living creature from where she was about to tread. Seeking moksha or spiritual liberation, the nun had chosen an ascetic life, eschewing all material possessions in order to overcome what the Jain faith considers the real enemies to humanity: ambition, greed, pride and desire. Those of this faith endeavour to inflict no harm on any living thing.

As I read of this practice, I pictured a wizened woman, her spine enduringly bent to this devotional task, and despite my own atheism was struck by what I imagined was a respectful and selfless dedication to a faith.

I don’t walk with a feather, but I do walk with a consciousness for what might be beneath my feet. Not just for those creatures on the surface (although I’m mindful of not stepping on those too) but for the billions – trillions – of creatures living in the labyrinthine landscape beneath it. I’m not fearful of harming these subterranean communities so much as acknowledging that this teeming, breathing, stridulating, reproducing, co-existing citizenry exists right there underfoot.

There is a character in my novel Bone Memories who also thinks a great deal about what lives in the soil. Billie has a deep emotional and physical connection to the ground where she lives; ground she once shared with her daughter Jess. Jess was murdered sixteen years earlier and Billie seeds this ground with the ash and grit of her cremated remains. She does this because she believes there is an ancient, unwritten agreement between the soil and humans: that all things come again through the soil, that the earth is a vast archive of all that has ever lived. This act by Billie is an attempt to revivify her daughter through the ongoing life and function of the soil. It is a belief that helps her in her grief.

I often think about how different our relationship with the soil would be if we were to think of it as Billie does: that it is the one thing making all of life possible, that it holds a record of all that has ever existed. Would we respect it more? Take greater care of it? Would we walk across it as tenderly as a Jain nun for fear of disturbing or destroying it?

*

In 2020, the Juukan Gorge rock shelters – a culturally and spiritually significant site of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura Peoples, who have occupied the site for over 46,000 years – was destroyed in the Pilbara region of Western Australia by mining giant Rio Tinto. I fluxed between disbelief, outrage and deep sadness at this wilful act of cultural vandalism. The disbelief quickly left me though. Because of course they did. There were eight million tonnes of iron ore worth 135 million dollars to extract from beneath the ancient rock shelters.

When Notre-Dame Cathedral, around 700 years old, caught fire in Paris in 2019, destroying a large part of its roof and spire, there was a world-wide outpouring of grief and an inpouring of donations to restore this globally recognizable and much-loved religious monument. I expect its restoration will be meticulous and as close to the original as is humanly possible to achieve. Being a structure on the ground it can be rebuilt, its symbolism will endure. But what of those spiritually significant sites like the Juukan Gorge rock shelters whose reverential value is embedded over millennia into its earthen floor and in the strata of its walls? How is that to be restored? The answer of course is that it cannot.

*

Carla, another character in Bone Memories who has married into Billie’s family, is a woman with an eye to the future and ambitions for a house that isn’t rundown or marred by the tragic events from her family’s past. Unlike Billie, Carla believes the earth is merely a solid foundation upon which to build a home and to raise a family, that it’s the people who live on it that makes a place special. I expect many would agree with her. The ambitions of these two women for what should happen with this shared ground are conflicted, their beliefs as divergent as religions. Carla is something on the land, while Billie is of it.

We were all of the land once. As a species we once revered and celebrated the extraordinary gifts the earth offered. It was a reverence passed down from one generation to the next. It ensured the continuity of a respectful and life-sustaining relationship with all biological and geological features on Earth – another ancient, unwritten agreement ensuring the continuity of human life.

As humans increasingly embraced Christianity they stopped looking to their feet, stopped revering the gifts beneath them, and lifted their gaze instead to the heavens for guidance. They stopped being a part of the singular earthly community and became a part of the heavenly one. This new community was forged largely by the patriarchy and colonial ambitions. Those outside these structures, those with little or no power or material wealth, lost out and so did Earth.

The character of Billie has no truck with religion or transcendentalism. She is what eco-theologian Thomas Berry calls ‘inscendent’. She lives an Earth-centred reality, denounces the post-colonial manipulation of the ground’s purpose to suit the individual, and seeks, instead, to reclaim her place amongst the earthly community; an association she feels in the very DNA of her bones.

Most people, like Carla’s character, live a human-centred reality. They believe that the places where they live, work or play for the hours, years or the lifetime that they occupy them, are theirs. They don’t recognise that Earth, having done much work to create itself, offers in its munificence something upon which all life forms can live, grow and thrive.

Except that tenancy is an increasingly faltering one.

*

We live on a changing planet. Future generations will be most affected by these changes. But how to give up the material benefits of a mostly unhindered existence? How to ask those future generations to essentially wind back the clock of progress when we – the older generation – were the ones who watched the clock hands tear around the dial, not bothering to pause and wonder at the consequences, despite many warnings that we should?

Thomas Berry says we are between stories. He says we have forgotten the old way to live but have not yet learnt the new.

The third narrator of Bone Memories is a young man trying to learn which story to live. Daniel is the son of the murdered woman, a crime he witnessed as a toddler but has little memory of, yet lives with the legacy of it every day through Billie, his grandmother.

Daniel must walk in two worlds: the human-centred one he was born into, and the one his grandmother would have him walk in: believing the soil is his touchstone to his dead mother; that through it she is immortalised. He is yet to make sense of his place in either world and doesn’t feel he can live his best life in one or the other until he does.

Future generations will struggle to live their best life too, certainly while human occupation continues to be so determinedly written into the land, without lightness or cautious existence.

To give hope to those who come after us, we need to start speaking our new story more determinably. More collaboratively. More boldly. And we need to act upon it as soon as possible. We need to look to our feet once more, make our touch on the earth as gentle and respectful as a feather.