Christie Nieman is an award-nominated author, editor, researcher and playwright. Her debut YA novel As Stars Fall was published by Pan Macmillan in 2014. Her short fiction and nonfiction has appeared in journals and magazines including Meanjin, Overland, TEXT and The Guardian. She has been a contributing editor on the anthologies Just Between Us, (Pan Macmillan 2013) and Mothers and Others (Pan Macmillan 2015). Her critically acclaimed play, Call Me Komachi, received a Green-Room Award nomination, multiple productions, and publication by the Australian Script Centre. I interviewed Christie about her writing and current doctoral studies in ecocritcism, which she is undertaking at La Trobe University in Victoria.

In your short and long fiction, nature and the human condition tend to be inextricably linked. What comes first in your writing – attention to the natural world or the human themes you wish to explore, or is there a symbiosis in which one can’t exist without the other?

For me, a setting often presents itself first, a place. But from there I think that the stories that get drawn up out of the ground, of humans and other living things, they all seem to happen together. I can’t quite pull the two things apart. And that feels quite natural to me, I’m not sure why. Also, nature and the human condition are inextricably linked. It just feels like realism to me when I write. So I think it must be the latter.

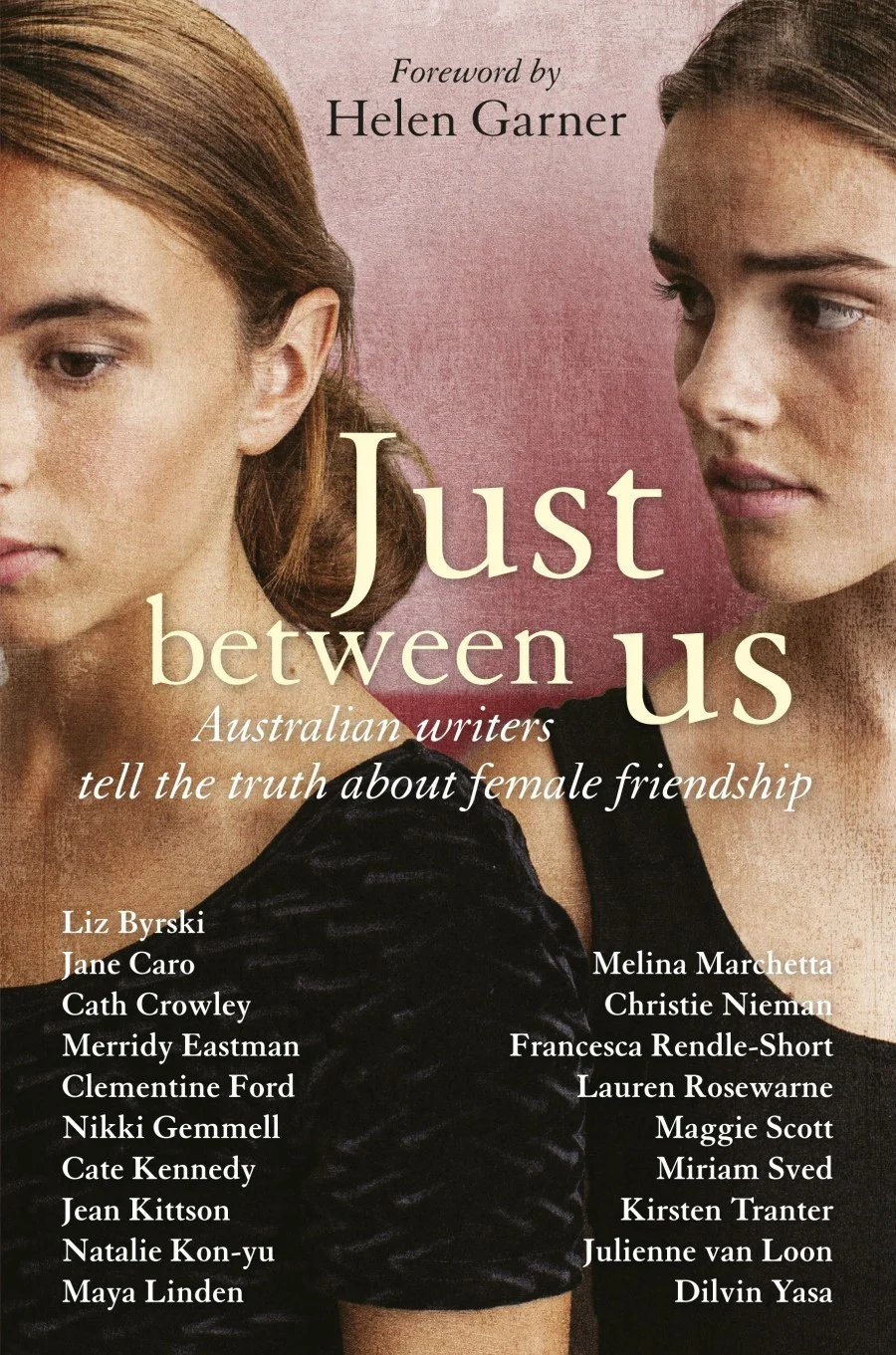

Your YA novel All Stars Fall (Pan Macmillan, 2014) draws parallels between emotional and ecological traumas. Your short story Magpie Wars (TEXT Journal. No. 20, October 2013), concerns itself with the impact humans have on the environment and the sacrifices one couple are prepared to make to minimise it. And in your short story, ‘The Young’, which appears in the anthology Just Between Us (Pan Macmillan, 2013), nature intersects with friendship and fertility. Have you always had an interest in environmentalism or do you recall some moment in time or a particular event that prompted you to address themes related to it in your writing?

I feel ill-at-ease with the term ‘environmentalism’ being associated with my work. Partly because it feels like taking credit for other people’s work – I’m not an activist, and without active environmentalists so many important and beautiful things would have been left open to destruction and so many rights left unprotected. But there is a lot about the term ‘environmentalism’ which doesn’t fit with the way I think. I conceive of my work and my role a bit differently. Something about essentialism and nonessentialism, certainty and uncertainty. But, to answer your question, I guess I’ve always felt embedded in the natural world, which I think comes from being a country kid with unusual freedom and licence from a very young age to go out and explore the world on my own (as long as I took the dog with me and as long as I turned up home at some point). So perhaps I had this predisposition, if you like, to view the natural world as my very good friend. And then in my twenties my scientist future-husband explained the intricacies of evolution to me and a great shift happened in my thinking. We’re not either close to or distant from the natural world, we are the natural world, and at the same time, there is no unnatural world. I couldn’t really shake it. Reading Darwin, or Timothy Morton, or Dawkin’s writings on evolutionary biology will have the same effect, if you dare.

American YA author Carolyn Parkhurst says of writing teenage characters:

“The challenge lies in erasing those layers of reminiscence. You can’t write as an adult who remembers how everything seemed immediate and unchangeable and a matter of life and death; you have to write as a kid who doesn’t yet know that it will ever feel any different.”

Did you have to remain vigilant when you were building the worlds of your teenage characters in All Stars Fall to prevent your adult voice overwriting those of your teenage characters? Were there any specific challenges you encountered in creating them?

I had a bit of a cheat with As Stars Fall because I started writing the character that turned out to be Robin in my late teens. So the teenage me had already set up her voice quite naturally and when I picked the character up again over a decade or so later it was like I’d left a door open in my adolescence and I could just walk back through it. Seth and Delia were different, they were more my adult creations, and I wonder if writing them in the third person allowed me to avoid that specific challenge. But yes, certainly I pay attention to the language and thought processes of the characters to make sure they have integrity, that they’re not me – but I would say that is true of all writers and all characters that aren’t that writer, rather than it being age-specific. Teenagers, like adults, are not a homogenous group – there is no way to write teenagers, only ways to write characters. But I was definitely aware of being vigilant in As Stars Fall that the characters were not mere mouthpieces for something I should write in an essay instead. That’s why I write essays – so I don’t have to corrupt a character. Because the art and beauty of fiction, the addictive art and beauty of writing fiction, is to say the thing you really want to say without saying it.

In an article you wrote for Overland Literary Journal (‘It’s no Hunger Games’, Issue 225, Summer 2016), you spoke about your disappointment that publishers in the US and the UK deemed All Stars Fall “too quiet” for their young adult market. And yet the story concerns itself with universal issues relevant to all ages: death, grief, loneliness, friendship and environmentalism. How as a writer do you reconcile the demands of the market with personal demands to represent the themes that are important to you? Do you think Australian publishers are more open-minded about the representation of the interior lives of teenage characters or are they also focusing more and more on teenage responses to apocalyptic events?

Any discussion of the market kind of leaves me gawping like a fish. I try to think of intelligent things to say, but actually, I find I really don’t understand it. It’s a big mystery to me, the whole thing. Publishers like good work: I really think that is their number one priority, so I’m not as cynical as some on that front. But I do think that the next tier down, after good work, where all the other pressures converge – of running a business, producing a product, and trying to sell it and stay afloat – is where the real squeeze happens, and I don’t pretend to understand the exact nature of those forces. So I don’t try and reconcile my work to the demands of the market. I work part-time instead so I don’t have to chase money with writing.

You create a strong sense of place in your writing and incorporate many sensate elements from nature in your work. Is your writing space conducive to this? Can you write anywhere or do you need to closely connect with the places you write about to fully realise them?

My writing space is conducive in as much as it is quiet and it is mine. Which actually means a lot. I also, as I drive around, often pull my car to the side of a road while I note down things about a place that has struck me, like the light of the time of day in that certain spot, or the way that group of birds behaves together under that tree. And if I know I want to set something in a specific place, I go and do some fieldwork. It’s good to get out.

You’re undertaking doctoral studies in creative writing and ecocritcism at La Trobe University. Could you explain the term ecocriticism and tell us a little about how it applies to the project you are working on?

Ecocriticism is a literary criticism stemming from environmental philosophy. All literary criticism looks at the literature of the day and applies different philosophical lenses to see what it can tell us about ourselves. You might use a marxist lens to examine embedded class structures in a work and, by extrapolation, the wider society in which the work occurs. Likewise you might use feminism to uncover gender disparities and mis/representations. And so it is with ecocriticism: ecocritics use ecological science and environmental philosophy to examine the ways we represent the nonhuman world in our stories.

My PhD is about how our fictions have historically used the natural world merely as backdrop, utility, or confounder to our own interests: a majestic mountain that must be conquered, and we might shoot some deer along the way for our food. Essentially we have colonised our natural world in our literature the same way we have in life. In other isms this colonisation usually means that we should stop appropriating stories from those we have colonised. But my argument is that ecocriticism is different to post-colonialism and feminism in that this doesn’t mean we should stop writing the natural world. We must write it, because we exist within it and because it can’t write itself. But my thesis is that we need to learn to write it differently, to notice the natural world in our human stories, not to mention in our human selves. My argument is that we need to really notice it, and include it, and acknowledge that every aspect has its own integrity and agenda, and stop keeping it so separate, so over there, the way we have in the past. Because that’s kind of what’s going wrong in the world, isn’t it? That we often see everything that isn’t us as backdrop? Or as something for us to either use or defeat?

Who are your go-to people to remind you of why it is you write and who you think help you be the best writer you can be?

I have the best writer's group. No matter what time of day or night they are standing by in virtual space to engage with whatever crisis-of-confidence, wobbly draft, out-there proposal, or general writing-life difficulties that come up. They are a bunch of smart, funny, forgiving, sharp-eyed, brilliant, talented, tell-you-what-they-really-think humans. This would be a much harder job without them.

On the page I find those reminders everywhere, in the work of a friend, a great short story that pops up, incredible novelists and thinkers; Atwood, Toibin, Du Maurier, McEwan, Hartnett, Pullman. Anyone who has a really interesting idea, and who expresses it in an arresting and engaging and intelligent way, or who really takes the time to drill down into the centre of something, has my aspirational heart beating faster.

What have been the greatest obstacles you’ve had to overcome in your writing?

My own idiosyncrasies. As Alain de Botton suggests, we should not be asking each other if and how we are normal, but we should enquire, with great specificity, ‘In what ways are you mad?’ My greatest obstacles have been the particular ways in which I am mad. (And ‘overcome’ is a very optimistic word here.)

Oh, and balancing time and money.

What's the one thing you wish you'd known when you first started out as a writer?

Success as a writer doesn’t look the way you imagine it does. And, ultimately, that doesn’t matter.