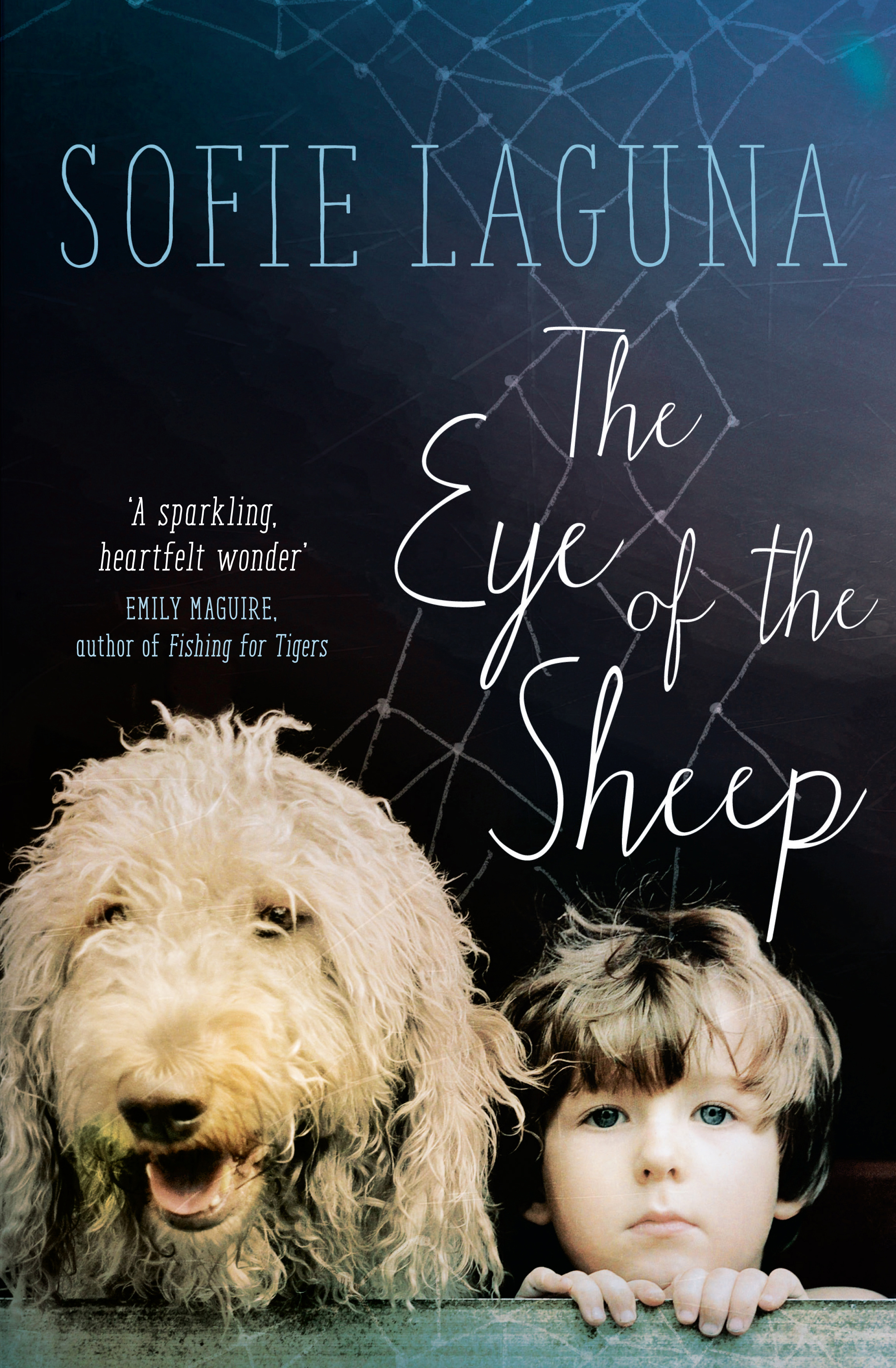

The Eye of the Sheep by Sophie Laguna and Leaving Elvis And Other Stories by Michelle Michau-Crawford

The Eye of the Sheep (Allen & Unwin 2014) by Sofie Laguna won the 2015 Miles Franklin Literary Award. Leaving Elvis And Other Stories (UWA Publishing 2016) by Michelle Michau-Crawford is a debut collection of connected short stories. The eponymously named story in Michau-Crawford’s collection won the 2013 Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize.

The Eye of the Sheep is about a boy and a family living with what is assumed to be an autism spectrum disorder. Leaving Elvis is about the legacy of hardship passed down through three generations of a family. In each book, the families disintegrate, come back together only to disintegrate again, as some families do.

Both books are quintessentially and unashamedly Australian and tackle class in Australia to an extent rarely seen. Laguna captures the urban industrial landscape of the working class and Michau-Crawford captures the rural one. Each is masterful in reproducing the colloquialism of the Australian language, and with great humour at times. But there is much more to these books than their irresistible portrayal of Australian life. They also explore themes which as a society we often fail to address.

The behind-closed-doors violence that occurs in some families is something many of us fail to build a narrative of understanding around. Often those of us fortunate enough not to live these experiences fail to grasp the complexities of the problem, or we look away. Not my problem, we think. Or we build a narrative of blame around the issue: it’s the woman’s fault for not leaving, or she probably deserved it, or it only happens in poor, marginalised or uneducated families, none of which is true.

These two books are important because what their authors have achieved is to sensitively inform their readers about family violence but without being didactic or passing judgement. Both writers gently and gradually build a narrative around this issue – the insidiousness of it, its causes and triggers and the patterns of behaviour peculiar to it that sees victims acquiesce to or be trapped by their circumstances. Both authors do this with grace, courage and honesty. And just as gradually an emotional awakening comes to the reader, by osmosis and not by force, as we fall deeper into the worlds of the characters within these stories and come to better understand their complex lives.

I felt safe in the hands of these writers. I trusted them not to sensationalise this important issue or to trivialise it. I admit I had to pause for breath in parts but not once did I want or need to look away.